Assisted reproduction has become increasingly common in the conservation of extremely rare animals such as the Spix’s macaw or northern white rhinoceros in recent years. In reptiles, on the other hand, there have only been a few studies on assisted reproduction, and only a few on chameleons in particular. Scientists from the USA have now conducted a study on male Veiled and Panther Chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus and Furcifer pardalis).

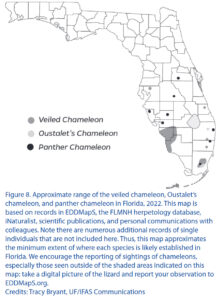

At Louisiana State University, 16 males of each species were kept under standardised conditions for over a year. The panther chameleons were purchased from a US breeder, the Yemen chameleons from a dealer who had taken them from the introduced wild chameleon population in Florida. All males were kept individually in ZooMed screen cages, equipped with automatic sprinklers and artificial plants. Temperatures were around 28-29°C during the day with spots to seek higher values. 12 h UV-B irradiation per day was offered. They were fed with crickets and zophobas.

Before the start of the study, all 32 chameleons were clinically examined and parasites were treated. Only after a month of acclimatisation did the actual study begin. During the study year, all chameleons were put under anaesthesia twice a month. Each time, blood was taken from the ventral tail vein or the jugular vein to determine the testosterone concentration. Ultrasound was used to measure the size of the testicles. In addition, each time an attempt was made to obtain sperm by electroejaculation. Electroejaculation involved inserting a small metal probe into the cleaned cloaca. Each chameleon was then treated up to three times in succession with up to 15 electric shocks of 0.1/0.2/0.3 mAs. The semen collection experiments were stopped as soon as the animal ejaculated. The sperm collected was preserved and examined for ejaculate volume, presence of sperm, sperm motility, concentration, and morphology.

The results suggest that Veiled Chameleons follow a so-called prenuptial reproductive strategy under constant husbandry conditions. The testosterone concentration in the blood already increased before the sperm volume of the males had reached its maximum. The months of May, April, and June brought the best sperm volumes, the most sperm was produced by electroejaculations in the third attempt. Testicle sizes also varied throughout the year, with the largest measurements from August to December.

Panther chameleons, on the other hand, seem to follow a postnuptial reproductive strategy. In them, most sperm could only be obtained well after the highest point of testosterone concentration. The electroejaculations worked best in March, April, May and June. Much more often than in Yemen chameleons, electroejaculation in panther chameleons worked already in the first attempt. The size of the testicles also varied throughout the year, but most were largest in the months mentioned above. Together with the factors mentioned above, the volume of ejaculate, sperm concentration, sperm motility and sperm morphology also changed during the year.

The authors recommend that electroejaculation in chameleons should generally only be performed under anaesthesia. The success rate for spermatozoa in the two highest cases was 82 and 88%, which is similar to the success in other reptiles during their reproductive season. The mortality rate among the 32 animals was only 0.12% over the whole year. One panther chameleon died after 10 months during the 20th anaesthesia, after death kidney damage was detected. From the low mortality rate, the authors conclude that electroejaculation rather does not play a role in the development of kidney disease, as was suspected in other studies. However, an examination of the blood for kidney values was not carried out on any of the surviving chameleons after the study. It also remains unclear what role the lack of imitation of rainy and dry seasons during the year plays for both species and their reproductive cycle.

Characterizing the annual reproductive cycles of captive male veiled chameleons (Chamaeleo calyptratus) and panther chameleons (Furcifer pardalis)

Sean M. Perry, Sarah R. Camlic, Ian Konsker, Michael Lierz, Mark A. Mitchell

Journal of Herpetological Medicine and Surgery 33 (1), 2023, pp. 45-60

DOI: 10.5818/JHMS-D-22-00037