For some time now, there have been various programmes and algorithms that can make various predictions about how many species in a country or region could be threatened with extinction in the future based on given data. Until now, this has always required a whole series of locations and data for the respective animal species as a basis. However, these are often not available for rare species.

Italian scientists have now developed an algorithm called ENphylo, which can make predictions from just two observations per species. It was tested in parallel to conventional algorithms on a model with 56 chameleon species from Madagascar. The occurrence and locations of the chameleons were taken from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Various scenarios of climate change and progressive changes in land use were modelled using CHELSA and other databases for the period between 2071 and 2100. For each of the chameleon species, 45 modelled predictions were calculated in the study.hnet.

As a result, the scientists predict a habitat loss of over 90% for the species Brookesia decaryi, Brookesia brunoi, Calumma globifer, Brookesia desperata, Brookesia karchei, Brookesia micra, Brookesia tristis, Calumma amber, Calumma guibei, Calumma ambreense, Calumma nasutum, Calumma fallax, Calumma peltierorum, Calumma boettgeri, Furcifer petteri and Furcifer willsii. As a result, these species would be directly threatened with extinction by 2100 due to climate change and changes in land use in Madagascar. The greatest area losses in potential habitats are expected in the dry forests of the west and north-west and the lowland rainforests of the east coast. The potential habitat loss is also expected to affect species that only occur in a very small distribution area but are very common there, such as Brookesia tuberculata.

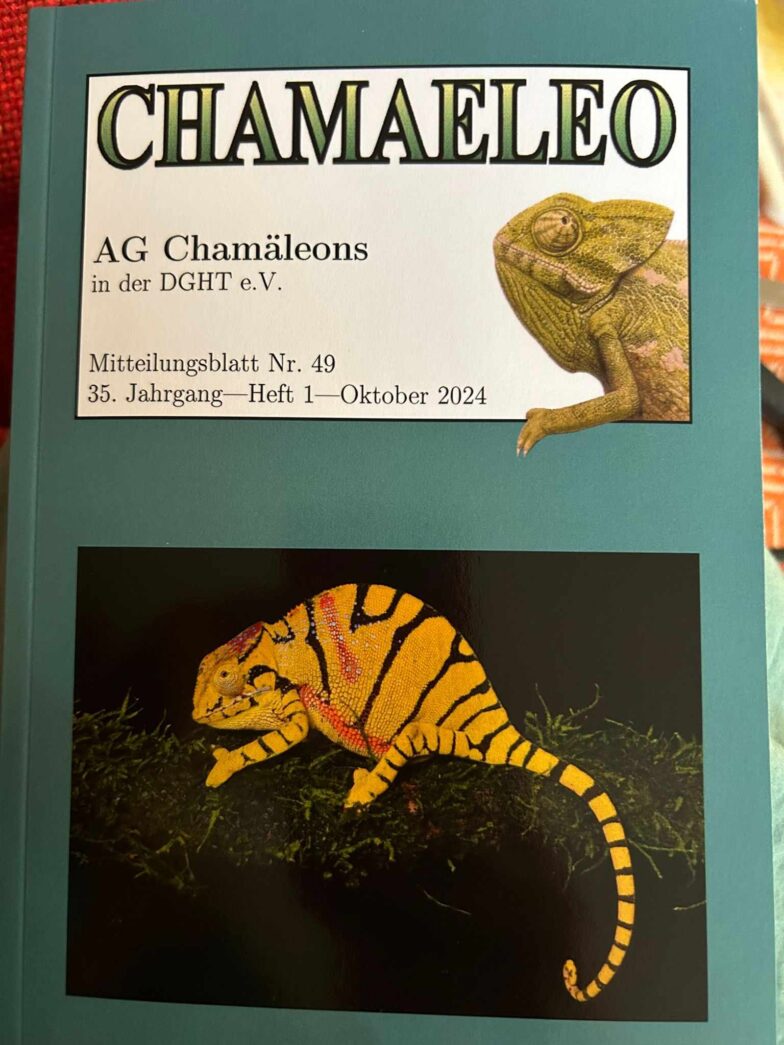

An increasing development of the habitat is only assumed for Furcifer oustaleti, Furcifer rhinoceratus, Calumma parsonii (unfortunately without indication of the subspecies), Calumma oshaughnessyi, Calumma crypticum, Calumma brevicorne and Brookesia supericilaris. According to the various calculation models, Madagascar could lose between eight and eleven chameleon species by the year 2100.

Modelling reveals the effect of climate and land use change on Madagascar’s chameleons fauna

Alessandro Mondanaro, Mirko di Febbraro, Silvia Castiglione, Arianna Morena Belfiore, Girogia Girardi, Marina Melchionna, Carmela Serio, Antonella Esposito, Pasquale Raia

Communications Biology 7, 2024: 889

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-024-06597-5

Photo: Calumma crypticum in Ranomafana, Madagascar, photographed by Alex Laube